Harry Nilsson’s 1971 animated TV special “The Point” is an unassuming thing- a cartoon which upon closer inspection is one of the most indicative examples of the Rollerwave aesthetic possible.

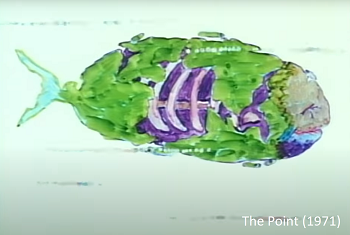

It resembles a segment from an early episode of Sesame Street or Schoolhouse Rock, which makes sense when you consider that it was animated by Fred Wolf, creator of the famous Tootsie Pop commercial with the owl. His sensibilities in bringing Nilsson’s album to life are fitting in that they convey a surreal, extremely colorful world with no fixed rules.

The story is rare in that it will appeal to both children and adults, far more than any segment from Schoolhouse Rock or Sesame Street. This is mainly due to the film’s theme of deliberate absurdity- that is, it is not designed to educate as much as it is to make the viewer think. These are two very different approaches. The Point is philosophical rather than methodical, it does not hammer any one particular idea into the audience’s head, and at times it is intentionally confusing, which is something you would not expect from a cartoon of this period.

The work most readily comparable to The Point is, of course, Norton Juster’s 1961 masterpiece The Phantom Tollbooth, in that, like The Point, its settings and characters are entirely allegorical. This method of storytelling seems especially popular around the 1960s and 1970s, rejecting the straightforward methods of the 1950s. The Phantom Tollbooth also contains vivid illustrations, particularly similar in their cross-hatching, messy ink style. Fans of Jules Feiffer will, I think, appreciate the style of Fred Wolf to an equal extent.

Some parts of this film draw attention to just how much we’ve changed as a society since the 1970s, and how much we’ve altered what is considered “acceptable” for children. During one abstract musical number, for instance, a dead whale is depicted, slowly rotting away, frame by frame. A modern viewer would see morbid imagery like this as only fitting in a Don’t Hug Me I’m Scared-type parody. In the 1970s, however, this was seen as not only acceptable to show children, but important, in that it adequately conveys the grim yet natural reality of death, and the cyclical system of nutrients in the ocean’s ecosystem. Other examples of children’s media being deliberately censored with the misconception that it would be deemed offensive include the infamous lost Sesame Street segment, “Cracks,” which was obfuscated during the 1980s cocaine epidemic despite having nothing to do with cocaine.

The Point, as I mentioned, is a philosophical fable with the key theme of societal acceptance and dehumanization. On the other hand, its title serves as wordplay, in that it asks what it means for something to have a point. By the end, the viewer is left asking themselves whether the cartoon had any sort of point. This element is aided by dialogue which is obtuse by design, and a meandering plot which attempts to defy the well-documented “Hero’s Journey” structure in favor of an episodic series.

The frame surrounding the tale is equally abstract, featuring a father who reads a bedtime story to his son, all the while sarcastically commenting about how “kids these days just want to watch TV” and his son views the story, presumably as the film itself, on the TV next to his bed. The father was voiced by four people across The Point’s broadcast history, two of which were Dustin Hoffman and Ringo Starr, and watching each version provides a somewhat different experience, given the varying inflections of the narrators.

This may very well be the ultimate animated Rollerwave film, ideal for anyone wanting to know more about the visually artistic side of the aesthetic, departed from live-action. It is inspiring for anyone looking to enter the realm of 2D animation, with its detailed landscapes and vibrant color. One can only long for this period, when animating a full album and bringing an hour-long narrative to life using nothing but pens, paper, and watercolor paint was considered routine. The result is well worth your while.