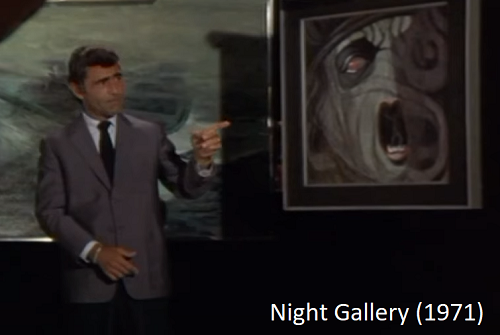

All of us enthralled with horror and speculative fiction have, at one point or another, wanted to visit the Night Gallery in real life. You can’t deny the pull of these accursed paintings- masterfully brought into being by Tom Wright, they go today for thousands of dollars, each one a captivating original which represents a well-written tale of the paranormal or occult. And if the Night Gallery were a real place- a tangible museum rather than a manufactured set- it would attract thousands who wished to explore its dimly lit passages, with the captivating Gil Melle tune beeping and reverberating throughout.

Many have accused Night Gallery of failing to live up to Rod Serling’s grand vision as a playwright, yet it contains all the proper Serling elements which made Twilight Zone such a hit initially. While it lacks much of the moral and philosophical nuance that have made Twilight Zone a timeless classic, I don’t think Night Gallery was ever intended to carry the same tonal weight, and I believe its lighter, more playful, anything-goes attitude is actually a benefit.

Today, Night Gallery is indicative of a bygone era, which only props up its surreal, abstract intentions. The artistically inclined theme the show carries is no accident- this is the ultimate anthology series for the countercultural discontent of the early 1970s. Its editing is spastic, stories end on a dime with no definite resolution, the cinematography can become disjointed and trippy at points, and behind it all are some of the best celebrity performances you’re ever likely to witness, from the likes of Roddy McDowell, Sondra Locke, Joanna Pettet, Burgess Meredith, Rene Auberjonois, and more.

While science-fiction episodes are rare, when they do appear, they’re great examples of the Rollerwave aesthetic, featuring technological bravado that could only have sprung from the imagination of Serling and his team. The segment “The Nature Of The Enemy” is what first inspired me to write this entry- set within a NASA laboratory during moon contact, it features the optimism of the Space Race, well-polished technicians and rows of beeping consoles, all coordinated to achieve lunar domination. Today, this fanatical dedication to spatial conquest is almost unbelievable. The gap between Earth and the Moon is palpable, held together only by thin radio signals and a blurry image on a screen. I won’t go into the plot here, but suffice to say, this is some of Rollerwave at its finest.

Or take “The Little Black Bag,” featuring what I believe is a deliberately corny interpretation of 2098, complete with radio headset and computer. This is not only one of Burgess Meredith’s finest roles, equally on par with “Time Enough At Last,” it may be one of the greatest science-fiction episodes of any show, ever. It’s a tale of technological disparity and man’s cold inhumanity to man- a story which draws an ultimately misanthropic conclusion regarding our inability to exercise responsibility and good judgment when endowed with privilege. Its final scene is deliciously morbid.

The greatest example of the Rollerwave aesthetic at work, however, comes up in the episode “Tell David,” wherein a woman is lost during a drive in the middle of the night and inexplicably travels forward in time from 1971 to 1989. An eccentric couple, David and Pat, living in a modern home with equally modern accommodations, show her such technological wonders as a computer phone and a gorgeous radio beeping out electronic tunes. The greatest achievement on display, however, bar-none, is one of the most accurate predictions I’ve ever seen in any sci-fi, let alone from the 1970s. This episode features Google Maps.

Yes, you heard that correctly- Night Gallery, in 1971, predicted a computerized, satellite-driven index of street names, addresses, and geolocational data. This machine might appear quaint to modern audiences, however being 34 years ahead of its time (Google Maps wasn’t launched until 2005) it’s an insanely forward-thinking, practical apparatus. David, in the episode, is revealed to have an obsession with gadgets, one of his chief characteristics, likely stemming from the childhood trauma he endures as a result of his father’s murder and his mother’s subsequent suicide. His preoccupation with technological innovation and modernity is in all likelihood a means for him to escape the horrors of his troubled past. This is not stated outright in the episode, of course, yet it comes across well enough as a subtext. Little else should be said regarding the intricacies of the episode- rest assured, it’s one of the Gallery’s finest.

Here we must ultimately pass judgment on this show- does it constitute Rollerwave? I would argue that it does, at least when it attempts to tackle futuristic or scientific elements. These semantic concerns are ultimately what keeps this blog interesting- and why I began it in the first place. As a young, relatively unexplored genre, Rollerwave requires canonization- that is to say, an expert who can define what it is and isn’t. This expertise requires intuition, the ability to play it by ear, for the most part. Not all science fiction from the 1970s is Rollerwave- Alien, for instance, definitely isn’t.. By the same token, not all Rollerwave films are science-fiction, as is the case with Taxi Driver.

I would be remiss not to include Night Gallery here, it’s a quintessential assortment of quirky 1970s fashion and attitude, and is, after all, the namesake for this project. Yes, that’s how much of a sucker I am for this program. Make of that what you will.